Not a few hours go by, even when I was busy at work, that I do not think about Buntong Market, its people and my life there. Buntong Market was where I spent most of my childhood and teenage years. It was the commercial and social (aka gossip) center of Buntong New Village (文冬新村), a small village in the city of Ipoh in Malaysia. The market has different sections, for vegetables, fruit, seafood, meats, sundries, household items, clothing and accessories, toys, individual coffee shops, and a big food court.

My life in Ipoh began in 1979 when I was four. Before that, my family of six lived in a rented room in Kuala Lumpur, the capital city. One morning, five of us snuck out while the sixth was sleeping off his hangover. I am pretty sure it was my Uncle who came to fetch us. A few hours later, we were in our ancestral home in Ipoh. Shortly after arriving, we walked the two blocks to the market.

At the coffee stall in the food court, my relatives sold drinks, cigarettes, and beer. In a separate stall, they sold BBQ pork buns and loh mai kai (glutinous rice steamed with chicken). I don’t remember exactly when my mother started renting a stall across from the coffee stall to sell noodles with clear pork broth soup, Assam Laksa (fish broth with tamarind) and Coconut Curry.

I also don’t remember what I thought of the market and all the strangers that very first day, but I would come to know the market and the people very well. For all its good and very bad, I would come to love Buntong Market and Buntong.

Writing the text for the fundraiser I recently organized for Noah’s Ark Ipoh reminded me of a specific event there. When I was about ten, there was a meeting that involved all the food and drink vendors in the food court. It was about a fundraiser to help the victims of radiation poisoning in a nearby village called Bukit Merah New Village (红泥山新村); literal translation – Red Sand/Soil Hill New Village.

Situated in the Kinta Valley, Ipoh was an important tin mining town during the British colonial times. Malaysia gained her independence from the British in 1957. When the canned food industry switched to using aluminum for the cans the tin mining industry collapsed. Luckily or unluckily, the big mounds of slag that tin mining left behind in Bukit Merah contained monazite which contains a rare earth metal called yttrium. I don’t know if it’s the reddish brown color of monazite that gave Bukit Merah its name.

At the time of the fundraiser for the radiation victims, a company called Asia Rare Earth, which began operation in 1982, had been processing the monazite for a few years. The refining process generated radioactive toxic waste, containing thorium and uranium, which was stored in second-hand metal barrels left out in the open, sometimes uncovered. Some of the waste was even dumped into the pond next to the factory.

Foul smells lingered in the air; choking people and burning their eyes. Workers and villagers nearby started getting cancer particularly leukemia, and suffering miscarriages. Infant mortality, birth defects, and lead poisoning were common. It was for these victims that the fundraiser was organized.

On the day of the fundraiser, all the stalls were to set out a tin can into which customers would drop their donations instead of paying the vendor. If some of the vendors were unhappy about having to donate a day’s worth of capital and labor, they stayed silent until the day of the event when their closed stalls said it all. Looking back, I understand that some of them simply couldn’t afford to donate anything.

Most stalls were open, and most had a donation tin can out. The cans were made using empty Milo (chocolate powder) cans from our stall with a slot cut into the lid. Someone wrote things in Chinese calligraphy on red paper which was used to wrap around the cans. Posted around the food court were big banners about the fundraiser, and Chinese newspaper clippings for people to look at.

“Look at” because many of the people couldn’t read, or read proficiently. Or they were Indians who didn’t read Chinese. The Malay villagers almost never enter the food court because of the pork items sold there, although a few of them did buy drinks and cigarettes from us.

When the donation cans were emptied I saw quite a few red color paper bills. Those are 10 Ringgit bills; many times more than what most food items would have cost. Currently, 10 Ringgit is about USD $2.50. Nobody would tell a nosy kid how much was raised, but I remember feeling very comforted that there would be money going to the victims because the deformities shown in the newspapers really scared me.

I was surprised that there was actually money collected. While most people in Buntong were able to eke out a living, most of us lived in poverty, and many, in extreme poverty. So, I didn’t think people had any money to give away, but some did. People who were well-off, relatively speaking, donated generously, relatively speaking. Seeing so many poor people willing to help others opened the eyes of the ten-year-old me that day.

During my 16 or so years growing up in the market, I saw so much misery that many wouldn’t believe half of it. I’ve also seen acts of kindness, big and small, toward humans including the outcasts – the addicts, alcoholics, glue sniffers, prostitutes, an abandoned baby boy, the disabled, or the mentally ill.

These acts ranged from villagers chipping in to help pay for funerals; to my Uncle lending money to people he knew will never be able to pay him back; and to my Aunt, who no matter how busy or tired she was, politely giving a mug of hot water to a drug addict who needed it to go shoot up.

Very sadly, the stray cats and dogs in the market weren’t so lucky. That is, if you consider momentary relief during a lifetime of suffering to be lucky. Since I dealt with food and drinks, I almost never touched them. We gave them food scraps, and shooed them away whenever the few evil customers who would hit them were around. Nothing much beyond that, other than feeling pity for them; for the pregnant, nursing or sick ones, and for the abandoned newborns that hadn’t even opened their eyes yet.

There was nobody to call; no department, no organization. Maybe there was and I just didn’t know about it. I didn’t think there were people who cared about throw-away animals, or cared enough to actually help them. Until I was in my early twenties, I did not know that people brought animals to the doctor. Outside of school, life in my immediate circle was poor, nasty, brutish and short. Buntong was worlds apart from the many nice neighborhoods of Ipoh. I readily admit, other than being somewhat book smart and pretty street smart, I was a bottomless pit of ignorance.

Last year, at the recommendation of my schoolmate, Jessy, I followed Noah’s Ark Ipoh, an animal welfare group on Facebook. From the page, I learned that there is a group of dedicated animal lovers who work tirelessly to help the stray cats and dogs of Ipoh. When I came across a lady who feeds and TNRs (Trap-Neuter-Return) the dogs of Buntong Market, I was overcome with emotion. I wish she existed in my world all those years ago. Better late than never, they say.

We no longer support or endorse Noah’s Ark Ipoh.

However, it was too late for the victims of Bukit Merah. In 1984, thousands of villagers protested in support of eight villagers who sued Asia Rare Earth. Many of the protesters were arrested and detained without trial. Seven long years later, the Ipoh High Court ruled that the company must close within 14 days. It didn’t. It appealed the decision, and the Supreme Court of Malaysia sided with the company.

People went to Japan to protest outside Mitsubishi which owned 35 percent of Asia Rare Earth. Under pressure of boycott and bad publicity, Mitsubishi withdrew from the partnership, and the company had no choice but to close down.

The victims with cancer who were adults back in the 80s have since passed. A boy with physical and mental birth defects who had been featured in the newspaper clippings died at the age of 29 in 2012. His mother worked for Asia Rare Earth. She took care of him his whole life. His father abandoned them along with seven other children. The mother and son went with the group to protest in Japan, but were not allowed inside the Mitsubishi building.

Over the years, I thought about the Bukit Merah fundraiser often. When a few schoolmates died of cancer in their thirties leaving behind young children, I couldn’t help but suspect they were somehow exposed to the toxic waste dumped by Asia Rare Earth.

Now, the toxic waste has finally been moved to a hill and stored according to safety specifications although no local officials seem to know much about it. Before being moved to this hill, it was stored for about two decades on the edge of a small town called Papan; the same place where the City has been dumping the stray and abandoned dogs rounded up from around Ipoh.

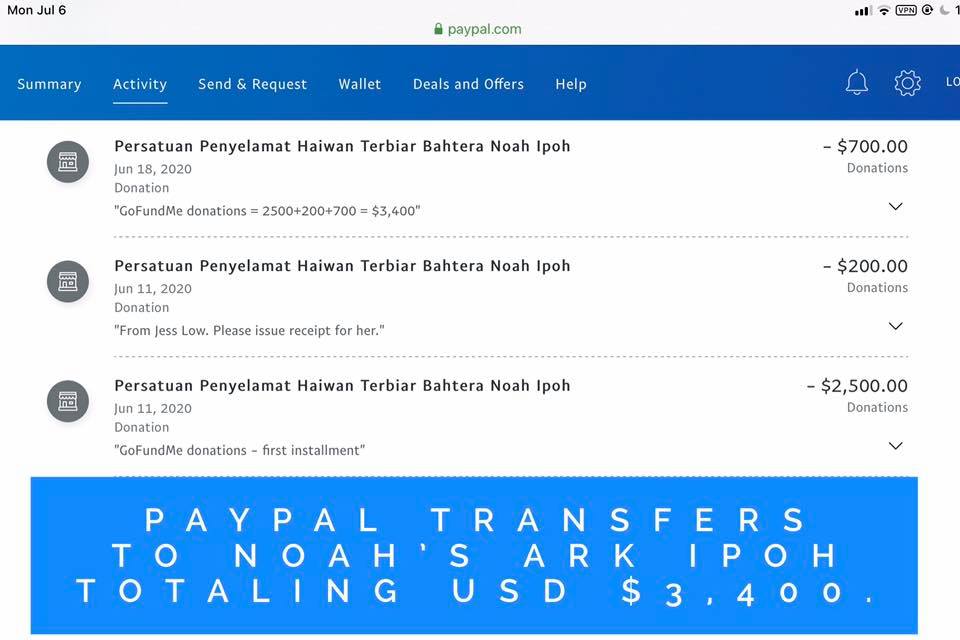

Some of you donated to the GoFundMe doggie fundraiser for Noah’s Ark Ipoh. I thank you very much, and also on behalf of the volunteers and doggies of Ipoh. Like those Buntong people who donated to the Bukit Merah fundraiser despite experiencing hardships themselves, you inspire me. The volunteers of Noah’s Ark are especially touched. Kenric and I have donated what we can for the moment to pay for the sterilization of the dogs. We are funding a separate small project for them which we will reveal if successfully completed. Fingers crossed.

I haven’t been hounding anyone about our fundraiser because of the current economic situation. I have sent the first $3,400 raised to Malika of Noah’s Ark. I’ll wrap up the fundraiser soon, but hope to raise a little more money for them. If you can, especially if you are Malaysian or from the Ipoh area, please chip in. We can’t stop every evil in the world, but we can stop innocent puppies from being born just to die. Let’s get these poor dogs sterilized, and let them live out their lives in a less horrible existence.